Introduction to direct democracy

Content of this page:

- Achieving net-zero carbone emissions with a democracy

- Conditions for collective intelligence

- Collective intelligence at work

- Limits of a centralized government to reach net-zero-emissions

- Vote proceedings

Outside the Swiss mountain communities, the idea of direct democracy originally came from the French Nicolas de Condorcet in 1790 and has been applied in Switzerland at the national level since 1850. This page brings little new information for readers from Switzerland, it is primarily intended for countries with centralized political structures without any elements of direct democracy.

"The sovereign, having no other force than legislative power, acts only through laws; and the laws being only authentic acts of the general will, the sovereign can act only when the people are assembled. People assemblies, it will be said, what a chimera! It’s a pipe dream today; but it wasn't two thousand years ago. Has human nature changed ever since? " Jean-Jacques Rousseau, From the Social Contract, Book III, Chapter XII

"Never before has there been a constitution in which equality has been so complete and in which people have protected their democratic rights to such an extent. [...] This equality allows the people themselves to exercise rights that were previously reserved for delegates, it turns all citizens into active legislators of the French state. They vote individually on laws or the revocation of laws. It is the most democratic constitution that can be given to a great nation." Frank Alengry; Condorcet, guide de la Révolution française; Slatkine Reprints, Genève, 1971

Achieving net-zero carbone emissions with a democracy

The authors Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt show in their book "How democracies die" how democracies can be destroyed from within. They are by no means the only ones who are warning about a steep decline of the quality of democratic debates. Achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 will considerably reduce the gross domestic product (GDP). That will not be possible against the will of the citizens without causing serious political turmoil. If we do not implement the necessary changes in our industrial societies quickly enough, serious climate crises would ultimately reduce GDP, against the will of all. Whether we like it or not, GDP will decrease one way or another. Achieving climate neutrality in a democracy in just 30 years is therefore a great challenge. Several Swiss referendums have shown that the population approves strong energy-saving programs (2017) and accepts the development towards a 2000-watt society in a local referendum (Zurich in 2008). The example of France shows that even smaller changes such as a small increase in the petrol tax are fiercely opposed (yellow-vest revolt) if they are imposed by a centralized, remote and detached bureaucracy.

Advertising in all media reminds us about 20 times a day that we are consumers. In democratic countries like France, we are reminded once every two years that we are also citizens that elect city councils or Members of Parliament (MP). This ratio of 1 to 10 000 should change as soon as possible if we are to create a successful transition to a post-oil society with democratic means.

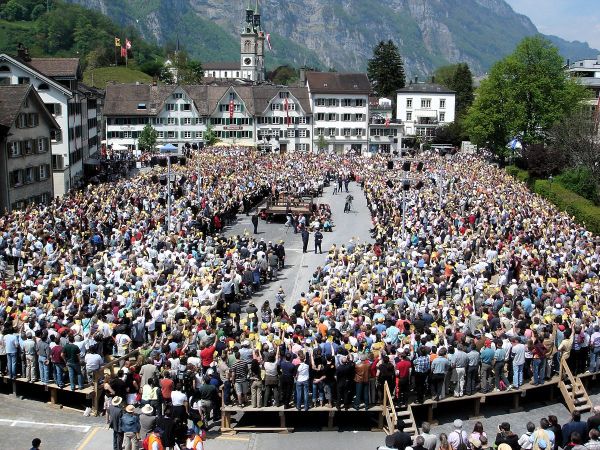

People's assembly in the county of Glarus. This is where laws, budget and county expenditure are debated and decisions are made directly and democratically. Any citizen can request the floor. This tradition is now 700 years old.Democracy needs citizens who participate and engage in public matters. The grumbling consumer-mentality does not produce lasting democracy, it favors democracy despising demagogues. In the history of mankind, no democracy lasted more than 250 years before relapsing into tyranny. Without the help of the United States, European democracies would have disappeared 80 years ago. Yet, direct democracy in Switzerland has a long history dating back to the 13th century. The mountain communities of central Switzerland had successfully fought the emperor's army. These mountain communities were then governed by popular assemblies and had developed the methods of democratic dialogue. That dialogue guaranteed their unity and independence from the Austrian Habsburg Empire. From the 14th century, the cities of Lucerne and Zurich imitated the mountain communities and built a mutual defense agreement with those communities. No other form of democracy has lasted so long without interruption.

People's assembly in the county of Glarus. This is where laws, budget and county expenditure are debated and decisions are made directly and democratically. Any citizen can request the floor. This tradition is now 700 years old.Democracy needs citizens who participate and engage in public matters. The grumbling consumer-mentality does not produce lasting democracy, it favors democracy despising demagogues. In the history of mankind, no democracy lasted more than 250 years before relapsing into tyranny. Without the help of the United States, European democracies would have disappeared 80 years ago. Yet, direct democracy in Switzerland has a long history dating back to the 13th century. The mountain communities of central Switzerland had successfully fought the emperor's army. These mountain communities were then governed by popular assemblies and had developed the methods of democratic dialogue. That dialogue guaranteed their unity and independence from the Austrian Habsburg Empire. From the 14th century, the cities of Lucerne and Zurich imitated the mountain communities and built a mutual defense agreement with those communities. No other form of democracy has lasted so long without interruption.

Communal intelligence: In 1907, the statistician Francis Galton made an interesting experiment. During an agricultural exhibition, he asked 800 volunteers to estimate the weight of a living ox on display. The mean value of the estimates was accurate by 1%, which an individual would only have achieved by chance. That's one case among many to show the intelligence of a group of people. Modern team-work is another form of communal intelligence.

In a culture of communal intelligence, a criticism has no more value than a counter-proposal to the criticized topic. With this in mind, the downloadable data and computations were made available in order to improve them together.

Conditions for collective intelligence

Different scholars have shown the value of collective intelligence among scientists, for example Isabell Stengers in her book "Une autre science est possible". In his book "The Wisdom of Crowds", James Surowiecki demonstrated the benefits of collective intelligence for management, financial markets and democracies. Collective intelligence produces better results than individual intelligence if it meets the following four conditions:

1) Diversity of opinion (each person should have some private information, even if it's just an eccentric interpretation of the known facts),

2) Independence (people’s opinions are not determined by the opinions of those around them),

3) Decentralization (people are able to specialize and draw on local knowledge),

4) Aggregation (some mechanism exists for turning private judgments into a collective decision) [1]. Swiss semi-direct democracy fulfills these conditions.

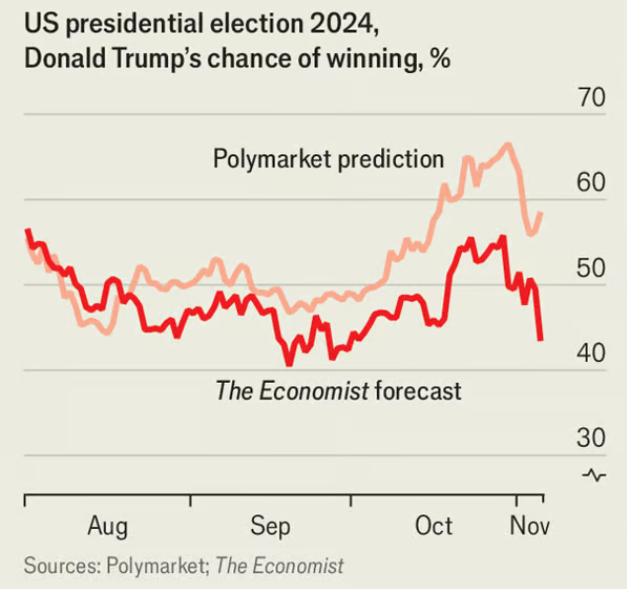

The Polymarket crowd made a preciser forecast than pollsters and pundits.The betting website Polymarket allowed anyone to bet about the US presidential election, choosing between D. Trump and K. Harris. The forecast of The Economist is usually one of the most reliable, yet the Polymarket crowd predicted the outcome of the election much better than did pollsters and pundits.

The Polymarket crowd made a preciser forecast than pollsters and pundits.The betting website Polymarket allowed anyone to bet about the US presidential election, choosing between D. Trump and K. Harris. The forecast of The Economist is usually one of the most reliable, yet the Polymarket crowd predicted the outcome of the election much better than did pollsters and pundits.

More recently, the users of Polymarket did a better job than other sources at predicting Israel's strikes on Iran. They did also a better job than polsters at predicting the result of New York's Democratic mayorial primary ! [2]

In direct democracy, if the subjects are suitable, scientists and other specialists participate in the development of arguments both with civil society and with Parliament, because more often than not, the best arguments win votes and intellectual laziness is punished at the ballot box. The fear that direct democracy is a form of "dictatorship of the demagogues" is unfounded. Switzerland is proof to the contrary since voting participation increases with the level of voters' education.

Direct democracy weakens some criticisms of representative democracy. Lobbies can influence or buy a few members of parliament, it is more difficult to buy a quarter of the population. Second, no Swiss political party dares to tell lies to win a vote like the outright lies told before the Brexit referendum. Such a lying political party would not be credible for a long time after the lies become obvious, like after the Brexit vote. With an average of eight votes per year, spread over three weekends, it is in the interest of politicians to remain credible in the long term. Before each vote, public television and radio organize debates, during which no one wants to be reminded of the previous lies. Could the Swiss democracy inspire other countries and contribute to get to net-zero-emissions with democratic means ? The purpose of these pages is to try to answer this question.

In order to compare the political cultures of Swiss and British citizens, this website proposes three Swiss votes, resulting from citizens' initiatives, with the arguments in favor and against each of the three bills. To start, we choose in the menu "Votes" the title of the desired proposition. After reading the proposed laws and the arguments in favor and against it, it is possible to vote "I vote for", "I vote against", "I have no opinion". If there are enough voters, the results can be compared with the vote in Switzerland and the press and the government may be informed about the results. But the Swiss citizens' initiative does not correspond to what some politicians are asking for France. In Switzerland, it is not possible to dismiss a politician or any other public person by referendum. It is only possible to make proposals for laws in accordance with the existing constitution. It is also possible to require a referendum for a law passed by Parliament.

For each citizens' initiative, the government can make a less extreme counter-proposal and put it to a vote at the same time. In Switzerland, the organizers have to formulate a proposal for a law and then collect 100 000 signatures within 18 months. Signatures and postal addresses are checked to see if the signatory has the right to vote. If the organizing committee of the citizens' initiative has respected the deadlines and the number of signatures, the bill must be submitted to a referendum, even if the government and Parliament are against it. The government and the Parliament can make a counter-proposal and submit it to a vote too. Proposals are accepted only if they win both the majority vote of the people and the majority of cantons, e.g., the proposal has to be accepted by at least 12 of the 23 cantons. Thus, a few large and populous cantons can't force their opinion on small rural cantons.

This website contains three voting-subjects of varying complexity.

Collective intelligence at work

The three propositions first give the text of the laws as it was sent to each citizen. Then, the arguments in favor and against the proposed law are developed. Usually the arguments "in favor" come from the organizing committee of the citizens' initiative, the arguments "against" most often come from the government and the majority of the parliament. Summaries of arguments are also sent to each voter. I chose three votes with three different levels of complexity. Readers will probably realize that people who do not like to think will not vote three time a year, which is not a problem for democracy and should reassure the government. Participation in complex subjects rarely exceeds 35%, but it is always more difficult for a lobby to "buy" a quarter of the population than "to buy" a few members of parliament. The system is therefore rather corruption resistant.  Information and debate before a referendum vote in the 2000-watt neighborhood called Kalkbreite.

Information and debate before a referendum vote in the 2000-watt neighborhood called Kalkbreite.

The citizens' initiative referendum could do good for the democracy of a country in which reasonable democratic debate has almost vanished and was replaced by name-calling and silly partisan criticism. In Switzerland, a criticism has no more value than the counter-proposal made to resolve the subject criticized. In Switzerland, the "full-time-critics" easily hear the answer "please start a citizens' initiative" or "what do you propose?". Even demagogues are forced to make concrete proposals, which puts them in a less comfortable position since their proposals can be criticized too.

Reaching net-zero carbon emission during the next 30 years will need plenty of propositions based on serious numbers and data. The figures and numbers given on this website should help to distinguish between demagogic green-washing propaganda and propositions that allow to reach the stated goal of net-zero.

Limits of a centralized government to reach net-zero-emissions

As shown in the book, centralized government can produce incentives for people to build better energy-efficient houses and offices. Carbon taxes may encourage companies to invest in renewable energy production. Centralized government can also encourage decarbonization of industrial processes such as steel production using hydrogen and electricity. SSAB, a Swedish steel company, has a large steel producing pilot-plant running that emits almost no CO2. Now, the company invests into a new bigger facility. However, as an IEA report from May 2021 shows, two thirds of CO2 reduction must be done by actively participating citizens that freely reduce their carbon footprint. A centralized democratic government has limited power to enforce drastic action on its citizens, many choices must come from the citizens themselves. Such choices can be implemented if a majority of citizens vote propositions in local referendums. In order for citizens to vote for carbon reducing propositions, they need practical examples such as 2000-watt neighborhoods. State bureaucracy must also show that they reduce their sometimes lavish living standards.

Sometimes a mayor or a governor behaves like a local god, spending lavishly other people's money on high profile projects, in total contradiction to the announced net-zero goal. For the good health of a democracy, it is therefore also desirable that high expenditure can be voted on by those who pay, the citizens. Elected officials automatically become more reasonable if they risk a setback at the ballot box for an expense deemed unnecessary or disproportionate. The citizens' initiative should therefore be able to ask for two things:

1) Demand a popular vote for a law passed by Parliament or for an expenditure voted by a municipal Council or a regional government.

2) Citizens' initiative should be able to propose a more or less precise framework law. If the proposition was accepted by a referendum vote, the details are then discussed and voted on by the (state) Parliament.

For each citizens' initiative referendum, the government can make a less extreme counter-proposal and put it to a vote at the same time. In Switzerland, it is necessary to formulate a proposal for a framework law and then, after verification of the constitutionality of the proposal, collect 100 000 signatures within 18 months. Signatures and addresses are checked to see if the signatory has the right to vote. This threshold of 100 000 signatures prevents about one in two citizens' initiatives from succeeding and being submitted to parliament and to a referendum. If the organizing committee of the citizens' initiative has respected the deadlines and the number of signatures, the bill must be submitted to a referendum, even if the government and Parliament are against it. But the government and Parliament can make a less extreme counter-proposal and put it to a vote as well. The number of signatures should be proportionate to the number of citizens of a country or state.

The Swiss recently voted in a referendum on a law to significantly reduce CO2 emissions until 2030. I have chosen not to propose a vote on this referendum on this website, because this law contains 53 articles and fills 70 pages. However, it is possible to download the bulletin that each Swiss citizen received before the vote. The booklet (in French) gives an idea of the complexity of certain subjects that the Swiss people discuss and vote about :

Votation-populaire-loi-CO2-13-juin-2021.pdf![]() 398.26 Ko

398.26 Ko

Vote proceedings

The three sub-menus first give the text of the law of each citizens' initiative as it was sent to each voter and put to the vote. Then, the arguments in favor and against the proposed law are developed. Usually the arguments in favor come from the organizing committee of the citizens' initiative, the arguments against it most often come from the government and the majority of the parliament. Summaries of arguments are also sent to each voter. I chose three votes with three different argumentative difficulty levels.

Usually, the debate is about giving a weight to each argument, rather than claiming that others' arguments are false. Sometimes the arguments are based on false data and if the data is corrected the weight of the argument is significantly reduced. The first debate should therefore allow the debaters to agree on the data. Then, in the process of weighing each argument, we usually find the philosophy of the person making the argument. Growing up and living with this kind of debates for a lifetime brings citizens closer to scientific methods and reduces the proportion of the population who subscribe to implausible conspiracy theories and "steal the vote" propaganda.

Without a culture of reasonable debate, democracy will probably move to chaos, followed by either state-oppression or a surveillance-state. Without a culture of reasonable contradictory debate, the terrible vision of society, described by Denys de Béchillon, French professor of public law, risks becoming reality:

"Whether we like it or not, half of the people - of this people who inspire the morals of the planet and which we should not believe is not like us - has made egoism its creed, renunciation of intelligence its principle, irresponsibility its rule and obscenity its style."( L'Express, December 16th, 2020).

This site hopes to demonstrate that this law professor is wrong and that another democratic outcome is possible.

At the start of the revolt of the yellow vests in France, before they brought violence to the big urban centers, I went to meet them on the roundabouts. There, I attended quieter and more reasonable debates than in some student meetings in the universities, although the discussions on the roundabouts were less eloquent. For a very long time, some students from the upper middle classes have been attracted to totalitarian ideologies (the ideologies of the Soviet Union and Maoism, Enver Hodja and Pol Pot, and today the Salafists), while the yellow vests asked for more democracy in the form of citizens' initiatives and referendums. That should not come as a surprise. In the 14th and 15th centuries, the democracy of the Swiss cantons was obtained by the struggle of the mountain peasants, not by the privileged classes of big cities like Zurich. The ruling and privileged classes of Zurich preferred the German princes to the democratic cantons "of deplorable poor mountain peasants", which are at the origin of the Swiss direct democracy. It is therefore not surprising that those who suffer most from the abuses of power by the powerful also demand more direct democracy in the form of citizens' initiatives and referendums.

Footnotes

[1] ˄ James Surowiecki, The Wisdom of Crowds, page 10. The author gives interesting and relevant examples in different fields. In "Crowd Psychology", Gustave le Bon shows the crowds are easily manipulated by demagogues. That type of crowds do not meet any of the four criteria mentioned by Surowiecki.

[2] ˄ The Economist, Prediction markets are soaring in popularity. With a few tweaks, thet could really take off; June 28th 2025